Rivers as commons: Reality or Myth?

The fact that most of the civilizations of the world flourished on the river banks is more or less uncontested. The examples of early river valley civilizations range from Indus civilization near Indus River to Mesopotamia along the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, Egypt on the bank of Nile, and Chinese civilization near Yellow River to name some of them. Even today most of the major cities of the world are situated on the banks of rivers viz. London near Thames, Paris near Seine, New York next to Hudson and the list is endless. Coming to the cities in India also, Delhi is on the bank of Yamuna, Kolkata is near Hooghly river, Allahabad at the confluence (popularly known as Sangam) of Ganga, Yamuna and mythical Saraswati, Ahmedabad near Sabarmati and many more.

Needless to say that there is an intrinsic link between the rivers and the human life in almost all parts of the planet called earth. For time immemorial, human beings have relied on rivers as source of livelihood in numerous ways. Navigation as a mode of transport could also become possible only due to presence of rivers as waterways. No wonder, rivers are even worshipped in countries like India. I intend to argue that rivers as commons[i] has long remained part of collective consciousness[ii] of the people but the advent of modernity with its stress on individualism seem to have challenged the erstwhile understanding. Its manifestation can be seen around us.

Advent of Modernity and the emergence of Modern Nation-State

Modernity as a socio-economic and political phenomenon, with a promise for ‘progress’ through reason, science and technology started in the post-medieval era in Europe and later reached the other parts of the world. So, is there just one notion of modernity or there are multiple modernities? Not going into the debates on modernity[iii], I would like to mention that overall it is the Western modernity which has a deep impact on the Global South. There are many facets of modernity viz. capitalism, industrialism, money economy and others but here I would like to focus on nation-states.

The formation of modern nation-state had manifold objective. As an actor it was supposed to plan the development, in other words how to best utilize the available resources – human population to natural resources viz. land, minerals, forests, water, mountains, rivers, etc. Not surprisingly, even the relationship between human beings and nature has changed drastically. With the advent of “modernity” and “progress”, now controlling the nature (by damming, mining, etc.) seem to have overpowered other socially and culturally significant aspects. Rivers no more remain just the source of livelihood or navigation or various other services that they provide but they are now utilized for electricity, irrigation, water supply, flood control and are dammed, diverted over long distances. The river beds are source of sand and gravel, as also dumping ground and source of land to be reclaimed for construction. The notion of control and maximization of extraction has become dominant and who gets what remains central to the idea of politics in general and applies to politics of rivers and water as well.

Contested Perceptions of Rivers

In East and North East India, states viz. West Bengal, Assam and Bihar often face floods and British rulers called the rivers bringing floods as ‘rivers of sorrow’[iv]. Frequent floods in some rivers and deforestation & degradation in their catchment areas has often led to numerous problems in these states. In a small booklet titled Tairne wala samaj doob raha hai, Anupam Mishra argues that floods have long remained part of human history but the perception of floods has changed in recent times. Earlier, people knew how to make use of the floods for their benefit and live with them, but now they are seen as disaster. To him, floods are natural and it is the modern way of thinking which has made us forget the friendly attitude of our ancestors towards them.

In South India, the Tamil people not merely take precautions against floods in the Kaveri river but they also celebrate the flood in the river with a festival called the Flood of the Eighteenth[v]. This celebration held on the eighteenth day of the month of Aadi (July-August), when thousands of people offer worship to the river by throwing offerings of fruits and flowers in the river water. They consider it a day of rejoice. We can find such practices in Bihar and Assam, as narrated by Dr. Dinesh Kumar Mishra. In the very same society there is a possibility of different perceptions of rivers, floods, water, etc.

Let us take up another instance of conflicting perspectives on rivers. The way State as an actor looks at river is very different from that of people. In the post-independence India, the Nehru’s celebrated call to see large dams as ‘temples of modern India’[vi] asked for a new way of looking at rivers. The idea of development so central to the project of modernity has shaped the course of action taken by the modern nation state in India as well. The very first five-year plan (FYP) provided for three major hydroelectric projects – the Bhakra Nangal dam in Punjab, the Hirakud dam on the river Mahanadi in Orissa and the Nagarjuna Sagar dam on the Krishna River in Andhra Pradesh. The Damodar dams were already under construction before that.

Big dams were justified in the name of collective good and since then the country has witnessed the construction of thousands of large dams on numerous rivers. On the one hand construction of large dams is a matter of pride for the modern nation-state in the name of development, but on the other it is also about the different forms of destruction, displacement, deforestation and violence[vii] that it brings. There is also issue of who takes decisions about such projects, using what process and who benefits. One of the longest battles against the big dam i.e. the Narmada Bachao Andolan could be seen in this light as to how people’s perception of rivers is very different from that of the State.

Case of Himachal Pradesh: What happened to the Rivers?

Himachal Pradesh is known for the beauty of nature in abundance. Recently, I visited Dharmshala and McLeodganj for three days and as my first trip to Himachal, I was very excited about it. But as soon as we started going towards the mountains from Pathankot (Punjab), soon we got disillusioned by looking at series of streams with hardly any water in most of them. From the locals, we got to know that the snowfall and rainfall has been very less this year’s winter and thus the availability of water in the streams is very low. However, the fact about the hilly areas is that the water in the streams increases from March onwards as the ice in the mountains melts in hot weather.

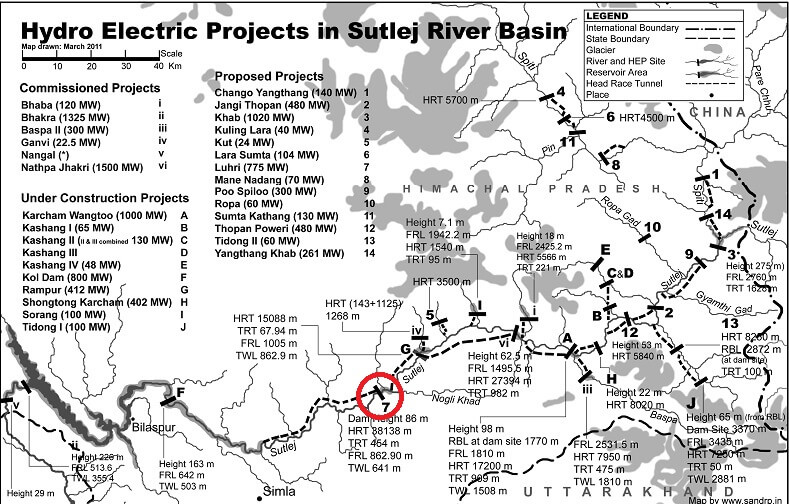

Following the grand project of development undertaken by the Indian state, Himachal Pradesh has in fact seen massive onslaught, starting from Bhakra dam. Rivers as source of water and locations for building hydropower projects are much eyed upon by the States. They consider themselves as rivers’ legitimate claimants and in fact they even act as owners. To be precise, we also had the case of Sheonath River’s privatization[viii] in Chhattisgarh. In Himachal Pradesh we see a different kind of river privatization where whole rivers are handed over to private and public sector companies for hydropower project development. Himachal today has the largest number of hydropower projects, and highest installed capacity, more than any other state of India.

So, from rivers as social and cultural entities and deities to river as private property. We have come a long way and the long held perception of ‘rivers as commons’ seems nonexistent in the overarching presence of the modern state as an actor or more of as a planner or developer or licensor. With its façade of scientific temperament and stress on controlling the nature, the rivers are reduced to merely as source of water and power by the State. It scarcely matters that rivers are living ecosystems and flowing rivers provide many services to the society and is habitat for large variety of flora and fauna. The floodplain of the river is often seen as a wasteland by the State and its agents. The series of illegal construction of buildings, especially the resorts with titles viz. ‘hill side view’ on the riverbed in Himachal is an apt example of that. Is such massive construction in hilly areas sustainable? In June 2013 Uttarakhand and in Sept 2014 Kashmir had massive flood disaster. In April-May 2015 Nepal had massive earthquake. Tourism as an industry is being pushed and after dams, now the states like Himachal and others are on another project of tourism development. There is the famous case in Himachal Pradesh where a politician diverted a river for his hotel, fortunately struck down by the Supreme Court, but many others have gone ahead, as was apparent during Uttarakhand flood disaster. We have the examples of Sabarmati riverfront (Gujarat) encroaching on the river flood plain and few more such riverfront development projects are in pipeline in other states.

To some extent, even the perception of ‘rivers as commons’ which was long imbibed in collective consciousness of the people has also dwindled due to modernity. Modern way of thinking and living has replaced the symbiotic relationship between human beings and nature with ‘nature as other’ and as mentioned earlier ‘nature to be controlled’. It is primarily a conflict between two world-views. But, we cannot say that the notion of ‘rivers as commons’ has become irrelevant. Numerous tribes in the north-east and other parts of India still worship rivers and mountains. To be precise, one may look at the case of Niyamgiri struggle in Orissa where the local people could fight the mighty MNC Vedanta to claim their right over the mountains. To the tribal, the Niyamgiri mountain is the representation of their deity but for the Vedanta company it is merely a source of mineral. In case of Niyamgiri, the Judiciary has accepted the tribal world view. In many cases, the Judiciary has accepted the public trust doctrine, but there are no credible well defined norms as to how this is to be practiced, say in case of rivers. Last year, the judiciary declared the River Ganga and Yamuna as legal entities but much could not achieved so far. Should we see this declaration as strengthening ‘rivers as commons’ or the individual rights of the rivers being more important remains a dilemma?

So where is the case of and practice of treating rivers as commons? What needs to be done to achieve that? Why have we not made much progress there? Why has judiciary not acted for achieving that? What institutions are there to achieve that? What institutions we need to achieve that? What changes we need in laws and decision making to make progress in that direction? Why has the society that seems to care so much for rivers has not cared to do anything to ensure that state treats rivers as commons? What role has media played in all this? Answers, unfortunately are not even blowing in the wind or flowing in any river. We will have to strive to find them.

Dr Ruchi Shree (jnuruchi@gmail.com)

END NOTES:

[i] The perception of water as a natural resource and the politics around it is shaped by various positions ranging from water as an economic good to water as a human right to water as commons. Here, I use of concept ‘rivers as commons’ to denote the worldview that they belong to everyone and thus beyond ownership.

[ii] Collective Consciousness is a concept often used in the various disciplines of social sciences but especially in Psychology and Sociology. It is “the set of shared beliefs, ideas and moral attitudes which operate as a unifying force within the society’ (Collins Dictionary of Sociology). The term was introduced by the sociologist Emile Durkheim in 19th cen. and later reformulated in 20th cen. by psychoanalyst Carl Jung who uses the term collective unconscious.

[iii] Scholars viz. Eisenstadt argue that in the post second world war period the modernizing societies refuted the homogenizing and hegemonic assumptions of Western model of modernity. Many of the third world countries such as India and others experienced ‘colonial modernity’ i.e. modernity came as a by-product of colonialism. Modernity gave primacy to what it recognised as scientific knowledge and thus other forms of knowledges prevalent in these societies were marginalized.

[iv] As early as in 1954, an article in EPW titled ‘Rivers of Sorrow’ narrates the havoc of floods http://www.epw.in/system/files/pdf/1954_6/35/rivers_of_sorrow.pdf

[v] The Story of Our Rivers, Part 2, by Al Valliapa, National Book Trust, New Delhi, p. 15.

[vi] A concept used by Nehru while inaugurating the Bhakra Nangal Dam in Punjab in 1954. He used the concept for the modern industries, steel plants, power plants, etc. Its not so well known that in a speech in Nov 1959, Nehru called blind push for big dams as disease of gigantism and advocated that irrigation and other benefits can also come from smaller projects.

[vii] One may read ‘Development and Violence’ by Ashis Nandy in his book The Romance of the State: And the Fate of Dissent in the Tropics, Oxford University Press, New Delhi (2003), pp. 171-181.

[viii] 22.6 km stretch of the river was privatized. One may read ‘Privatisation: In Chhatisgarh, a River becomes Private Property’, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 41, Issue no. 7, 2006.